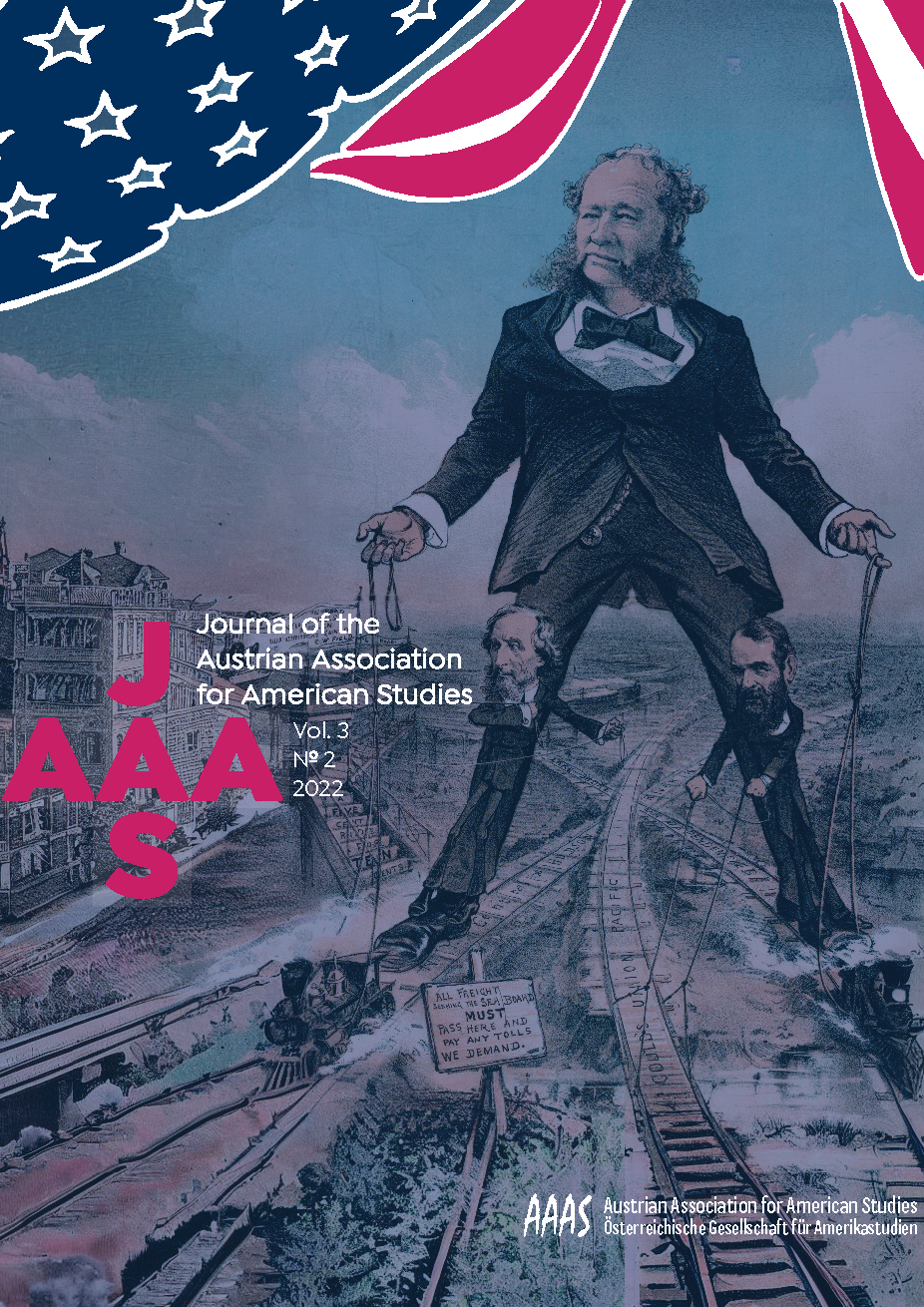

Volume 3, No. 2The American Entrepreneurial Spirit

Issue description

Calvin Coolidge is frequently remembered for having declared that "the business of America is business." However, this is slightly misquoting President Coolidge, who stated the following in a speech to a news trade group in which addressed the role of the news media in a free-market society on January 17, 1925: "After all, the chief business of the American people is business. They are profoundly concerned with producing, buying, selling, investing and prospering in the world." Despite being often misquoted, the president's proclamation cuts right to the heart of this special issue—the entrepreneurial spirit pervades American culture: from the All-American lemonade stand to the self-proclaimed dealmaker and business "genius" who was elected to the Oval Office in 2016. Consequently, entrepreneurial thinking and acting alongside its business practices, ethics, and legal customs and the attendant framework of cultural narratives, traditions, and beliefs undergird every facet of life in a free-market, capitalist system.

There is much that has been interpreted into the historical, seemingly providential coincidence of Adam Smith publishing his An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in the same year that the American colonies proclaimed their independence. Needless to say, the framers of the declaration were wholly unaware of Smith’s treatise, citing rather, as Thomas Jefferson recalled in a letter to Henry Lee in 1825, "the harmonising sentiments of the day," which were deeply indebted to John Locke and a largely Calvinist God who approved of the good works yielded by entrepreneurial activities. Consequently, when the United States declared the following truths as "self-evident"—"that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness"—they enshrined an entrepreneurial discourse in the foundational fabric of the nation. Thinly veiled by "the pursuit of Happiness" are the discursive formations of money, property, and, above all else, wealth, as means to elevate one’s own social status through entrepreneurial acumen and activity.

Laid out as essential human rights in the declaration, the US Constitution and the Bill of Rights not only essentially sanctify private property rights, but they also "created a political and legal climate conducive to economic risk taking," as Larry Schweikart and Lynne Doti put it in American Entrepreneur (2009). Therein, we find the latent spiritual dimensions of the entrepreneurial spirit which, in its zealousness, often bemuses and perplexes non-Americans. At the same time, it serves as some kind of "gold standard" for the business world as evidenced by the startup craze and the gig economy, which have infected the entire globe.

Bringing an American Studies point of view to a topic where it has been largely absent (being dominated by economists, social scientists, legal scholars, and entrepreneurs themselves), this special issue examines the American entrepreneurial spirit. The (hi)story of American entrepreneurs is, in a sense, the American story at large. As such, it not only cuts across, but also exposes the systemic (and unresolved) blemishes of the American national experiment with regards to race and gender, among others.